Articulation

Below, Mr. Wion links articulation to native language and provides ideas for exploring tongue placement.

Introduction

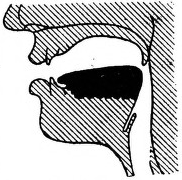

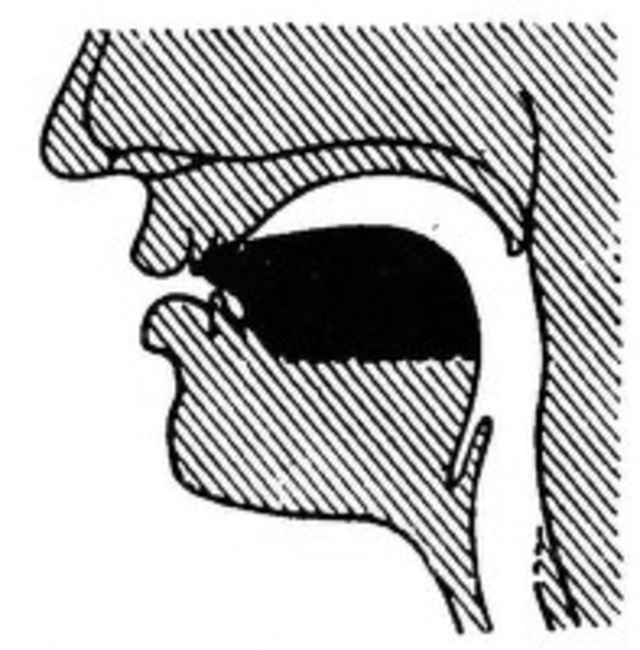

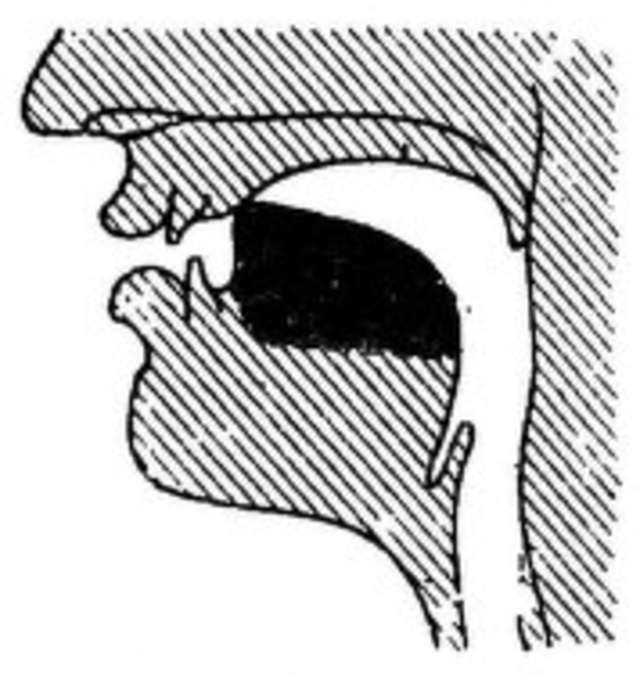

Natural articulation on the flute comes from native language. The French language, for example, is spoken very forward for both lips and tongue, and the consonant t is well defined. Americans tend to speak further back and t can become d or even lack any definition in speech. For this reason French flutists generally use forward or lip articulation, whereas most Americans tongue behind the teeth, on the hard palate. As one cannot fault the articulation of either Mr. Rampal or Mr. Baker, it seems reasonable that both placements are worth investigating.

First it must be recognized that an American wanting to articulate on the flute in the French manner will need to practice something that does not come naturally. The concept of spitting a grain of rice, or speck of sand, from the tongue-tip is a useful one. So is the concept of a champagne cork. Imagine the air pressure built up behind a tongue that is sealing the embouchure - when the tongue is pulled sharply back, the air flows immediately. If it is used at no other time, this is a wonderfully uninhibited and precise way to start a phrase. (I often sense that a student's tongue is getting locked on the roof of the mouth before playing, somewhat like a person who stutters. The breath is held, and the spontaneity of the music making is inhibited.)

However there are other relevant matters, such as size of lips, teeth, and tongue, which affect the optimal placement of the tongue in repeated articulations. For example, if you have a full upper lip and average teeth, you will see that when you make a playing embouchure and run your tongue-tip down the back of your top teeth, you will feel your lip, which has curled around behind the teeth. You can then be tonguing on the lip and still be tonguing behind the teeth. If your upper lip is less full, or your teeth bigger, you will have to reach forward between your teeth to make contact with your lip - obviously a different proposition. If you factor in a tongue that is shorter, or less pointed, trying to tongue on the lip, particularly in faster repetitions, can be counter-productive.

Still the concept of forward tonguing has universal value. The closer the act of articulation is to the flute the shorter will be the time delay before a sound is produced, and the easier it will be to coordinate the articulation with the breath impulse for a "pointed" start to a sound. With this in mind, investigate touching the smallest part of the tongue-tip, for the shortest possible time, against the part of the mouth (lip, teeth or palate) that is as far forward as practical and pulling it quickly back.

Keep remembering that the tone itself does not come from the tongue. Too often one hears a poorer quality of tone when a series of notes is articulated, compared to the same notes being slurred together. The tone production in both cases needs to be the same - the same impulse to the tone - the same embouchure. Articulation then is seen just as in language - defining the quality of the start of the sound, whether that sound is long or short. Playing long and short, slurred and detached notes in front of a mirror is a good way to see that the embouchure remains the same. Playing long tones without the tongue and then with the tongue will make it obvious if the act of articulation is changing the quality of the tone.

The normal goal of articulation is clarity. This involves precise placement of the tongue, its precise rhythmic use, and its precise coordination with finger changes. The tongue movement is minimal - not strong or effortful. Strong movements relate to special situations where accented attacks are called for, although even then accents are often more a matter of increased breath impulse.

If one is articulating a legato line, whether quick or slow notes, a continuous stream of air is divided by a precise movement of the tongue, just at the change of note (or repetition of the same note). If the tongue is prepared by placing it against the lip or palate too soon, the legato is lost. In avoiding this in a slow passage it is common for a student to produce a muddy attack on the following note. However, if the tongue is not returned to the striking position until the exact moment of need, and then used in a pointed way, both legato and clarity are possible. In repeated quick articulation the tone flow is also interrupted by striking the tongue too soon - and too forcibly. Quicker movements of the tongue do not mean stronger movements, which will also tend to move saliva into the lip opening. (If you are still spitting saliva into the embouchure try moving the tongue-tip back a trifle.)

If one is articulating a series of single, separate notes, those notes are each produced with a "puff" of air coordinated with the pointed articulation. When the notes come too quickly for separate puffs, the air stream actually becomes continuous, just as in the above situation.

In general these observations also apply to double tonguing. Although there may be staccato marks, that effect is best obtained not by trying to separate the sounds but by clearly articulating a legato air stream as described above. It is quite often the case that students will confuse an unevenness of fingering for one of articulation, and start tonguing harder to try and bring things together. Attentive practice of such a passage slurred will clarify any rhythmic instability, and remove any perception that forceful articulation is needed.

As one focuses the use of the tongue on the very tip the result will be that the rest of the tongue remains relaxed and low in the mouth. This in turn keeps the throat more open and relaxed, leading to fuller tone with less obtrusive vibrato. When playing high notes there is a tendency to raise the tongue and use it more forcefully as a substitute for producing the appropriate air stream. Although both of those actions will speed up the air going into the flute, the result will be a thinner, sharper tone. One useful practicing device to check this is to first play the high passage slurred, then copy the quality and pitch with added articulation. Another is to play the passage an octave lower, carefully noting the placement of the tongue tip and the strength of its action, then copy up the octave again without any change of tongue.

Clean articulation is a skill to be mastered, but beyond that remember that the tongue is a part of the way you express yourself, and its use is limited only by your imagination. There are places in music where a beautiful effect might be created by starting a phrase without the tongue, as in the opening of Debussy's "Prelude a l'Apres-midi d'un Faune", and places where legato notes might be better joined by softer, less precise articulations, or even breath impulses, as in the opening measures of Brahm's 4th Symphony where there are slurs over the rests, or the solo in the same movement (bar 95) where there are slurs and dots. And just as the tone you use in a French solo is inappropriate for a Bach sonata, do consider where and when a piece was written when you articulate it.