Phrasing

Mr. Wion’s extensive experience with operatic music and pedagogy provides him with unique insight into making beautiful phrases. Enjoy his insight below, which contains 16 examples from flute repertoire.

Phrasing implies direction.

When we express ourselves verbally we start with a thought that we then put into words. Depending on our level of education and the nature of the expression, the result might vary considerably in length and construction, but the appropriate amount of breath will always be taken, the stresses will be made in the correct places, and the quality of voice will relate to the emotion contained in the thought. Compare this to someone reading a text that they do not understand intellectually, or to which they bring no emotional involvement, and you see the difference that is often apparent between vocal and instrumental performers.

Expressive phrasing is rarely missing from a singer's performance but is often lacking in an instrumentalist's.

Telemann significantly wrote that whoever plays a wind instrument must be conversant with singing. With singing, composers' and performers' sources of expression derive from the words. Composers are inspired by the lyrics' basic emotional content and move the expression forward with appropriate melodic line, harmonic logic, and rhythmic stress. Performers use lyrics and their emotional content as a basis for recreating the composer's inspiration.

Flutists can learn much about phrasing from following the simple lines of beautiful arias and by imitating the ways that great singers express them. Look at how the opening of Puccini's "Un bel di, vedremo" (example 1) moves from the tonic down the scale on the first four downbeats. Then listen how great sopranos extend that line through intervening pitches and changing vowels, across rests, until the tonic is reached again on bar eight. (example 2)

By playing such arias with an understanding of both the narrative content and the musical direction we start to breathe in a more natural fashion, just as in conversation when we instinctively take the correct amount of breath for the length of the sentence, the distance of the listener, and the power of the emotion. We begin to use the entire period of each rest to breathe normally, instead of holding our breath until the last moment and quickly inhaling regardless of need.

We can similarly learn from vocal material that has been transcribed for flute, such as Boehm's arrangements of Schubert songs or Schubert's own use of his Trockne Blumen as a subject for his variations. One can usually tell whether a flutist has heard this melody in its original setting by the choice of tempo and sence of line. The 'singing' flutist will choose a slower tempo and will sustain the line with longer staccato and tonal weight on each note. Additionally, the emotional quality of the expression will be affected by knowing the text of the song. (example 3)

When playing instrumental music, not having the clarity of words as a guide, we have to find the logic elsewhere.

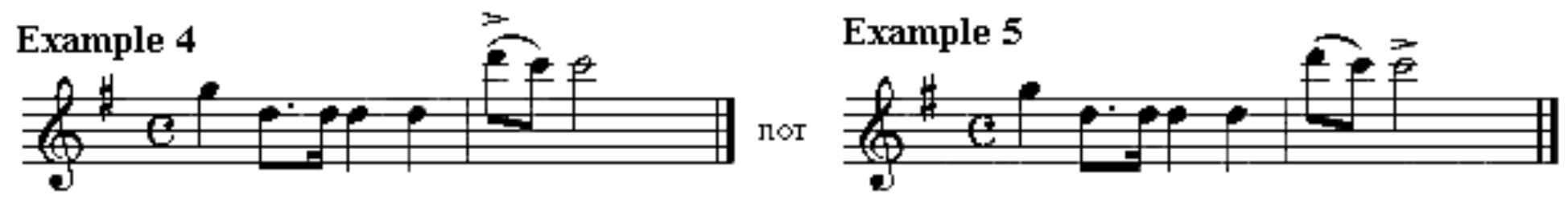

If we are not conscious of a musical direction when we play, off-beat notes may become stressed just because they are long and down-beats may be under-stressed just because they are short. (example 4) not (example 5)

Many flutists will not hear that bright notes need toning down in a particular situation, or that dull ones need to be brightened, and will allow the vibrato and dynamic to fluctuate without regard to the direction of the music.

Flutists are taught, for example, that closing certain keys on the instrument will produce a certain pitch, and that closing more keys will change that pitch. These fingerings relate more to notes on a printed page than to a musical interval, and the action can be carried out mechanically without thought. Singers, on the other hand, cannot sing an interval unless it has first been heard in the mind. Flutists' phrasing (as well as their intonation) will always improve when they start to "hear" the next anticipated pitch before actually moving the fingers, because the act is automatically leading them forward.

A simple musical phrase will usually rise to a single high pitch and decline again to its starting point. Sensitive musicians will intensify the sound to that high point (perhaps increasing the tempo as well) and ease back to the end of the phrase. Listeners will subconsciously be brought along a satisfying musical journey. More complicated instrumental phrases are not always as easily understood by performers. One cannot move the phrase in a logical fashion if its direction is not perceived, and the result will not be satisfying to listeners.

Simplifying such phrases is an excellent way to understand them. For example, the flute's four bar opening in the slow movement of Mozart's Concerto in D Major (example 6) can be simplified to G - A - B. (example 7) The A in bar two is repeated. (example 8) The As in bars two and three are delayed by G# appoggiaturas on the gown-beats, and the movement to B in bar four is delayed by an A# appoggiatura. (example 9)

Performers aware of this progression will see the D and B in bar one as an ornamentation of the opening G and move the phrase through those notes to the G# in bar two. That G#, reduced by ornamentation to a sixteenth note, will be lengthened and stressed to carry the phrase through to the A on beat two. That A, though a quarter note, is seen as a resolution and played lighter. Similarly the long A in bar three is under stressed, and its following C leads forward to the stressed A# in bar four. (example 10)

Another way to perceive this snese of forward motion is to group all the notes following a beat with the next beat, rather than the written beat groupings. Musicians who perceive the notes following each beat as belonging to that beat tend to play in a static fashion, whereas the perception of the afterbeat notes leading to the next beat, like grace notes, gives a powerful sence of direction. (example 11)

A flutist sensitive to phrasing will also use an even vibrato. A common fault with flutists is to start a long note without vibrato, then quickly introduce a noticeable vibrato for the remainder of the note. The result is an illogical and unsatisfying phrase because of the effect of these surges in inappropriate places. Players who truly see the direction of a phrase will not play in this disruptive way. This does not mean that an equally modulated vibrato throughout a musical line is implied. Vibrato is modified in both speed and amplitude, and notes within a phrase may be expressively colored thereby. An uneven vibrato, an excessively wide or slow vibrato, or an erratic vibrato, will have a considerably disruptive effect on a phrase. This is also true in a moving passage when a player uses vibrato. A pulse can coincide with a particular note giving it an unintentional accent that interrupts the musical line.

Rubato, and Italian word meaning 'robbed', is use in music to describe the taking of time from one part of a phrase and giving it to another. This implies firstly that the performer has a very clear sense of basic tempo. Rubato then becomes an expressive device whereby the tempo is moved evenly, and often imperceptibly, forward or backward to increase tension or to heighten emotion, and eased back with similar evenness. Rubato is only successful when the movement grows out of a tempo, the way a human pulse can quicken, and is awkward when there is an uneven progression to a different speed.

Absolute rhythmic accuracy is often counterproductive to expressive phrasing. In the opening of Debussy's Prélude à l' après-midi d'un faune, an exact duplet followed by an exact triplet will be less expressive than if the first note of the triplet is slightly longer and the third slightly shorter. (example 12)

This phrase is a good one to observe many of the subjects we have been discussing. In bar one, the C# leads forward with a slight increase in dynamic and amplitude of vibrato to the B. The B then falls toward the G because each note is slightly quicker than its predecessor. Both dynamic and tempo then ease back to bar 2. This bar has similar direction but with slightly more exaggeration toward the G. The last three notes in the bar however, instead of easing back, lead forward to bar 3. From this bar one must show the phrase leading from the C# to the B on beat three and away to the final A#, avoiding the common disruptive emphasis on the upp G# or even a breath after the E.

Some performers are mistaken in their approach to avant-garde music in similar fashion. They will apply strict rhythmic accuracy to groups of same value notes when a more effective 'gesture' will be obtained by a very slight accelerando, ritardando, or rubato.

Just as one can simplify a melody to see a progression of key pitches, one can connect various voices within a solo line to aid the snese of phrasing direction. In the Poco adagio movement of C.P.E. Bach's Sonata for Unaccompanied Flute, one can discover two or even three voices, as in the example 13.

In the Allemande of J.S. Bach's Partita, much thought can be given to such connections. While many will be obvious, other are less so. In the following example the dominant D is implied as sustaining until moving to its (implied) tonic G, creating a three bar phrase. Players who understand this will only break the phrase with a breath if absolutely necessary, and will then do so in such a way that the direction of the phrase is kept clear. (example 14)

Here the leading tone G# is implied as sustainin for four beats until its (implied) resolution to the tonic A. However, the tonic chord on the first beat of bar 37 begins with the upper and lower neighbour of the C and the tonic A is not heard till the second beat. Players who understand this will not breathe after the first note of bar 37. (example 15)

Whereas some instrumental phrases are clearly separated with rests, many cases exist where no rests occur. In these places melodic fragments must be perceived as separate entities and not run together. The Sonata in B Minor by J.S. Bach offers many examples of this, including example 16.

Phrasing instrumental music, then, has two elements.

The first is a musical one, finding the logic that led the composer to create the phrase. The second is a technical one, finding the means via the instrument to convey the musical loginc to an audience. The first involves meter, harmony, and form, while the second involves dynamics, nuances, vibrato, and rubato. As so often happens, the two are interconnected, and understanding of the first will lead to an appropriate use of the second.

What phrasing means to most people is the expressive, singing quality that enriches a simple melodic line so that it touches the soul. Imitation is one of the most powerful learning tools, and the sustaining and shaping of operatic arias is an excellent way for a flutist to develop phrasing awareness and acquire control. Knowing the specific emotional range of an aria from its words leads us to strive for a quality of sound and use of vibrato and rubato that will carry those emotions through the flute to an audience; imitating the instincts, skills, and artistry of the great singers as they express these emotions can lead us down a path of limitless possibility.